By pure definition graphic design and behavioral science may seem like two very different areas of study with very little connection to each other.

- Graphic design is defined as: The art and profession of visual communication that combines images, words, and ideas to convey information to an audience to produce a specific effect.

- Behavioral science is defined as: The branches of science (such as psychology, sociology, economics or anthropology) that deals primarily with human action and often seeks to generalize human behavior in society.

However, by utilizing behavioral science principles when practicing graphic design, the result is a more cohesive, higher quality design.

Your design not only looks good, but can increase the impact of the message you are presenting and drive the behaviors of the audience. In fact, many marketing firms and advertising agencies are already utilizing these concepts in their designs to increase the effectiveness of everything from how you shop to what you buy, how you perceive a product or idea and much more. These trailblazing concepts are shaping the world around you and by utilizing them in your own designs you can drive the level of impact you are having when you communicate to the next level.

Here are two ways YOU can start using behavioral science RIGHT NOW to optimize the impact of your designs and join the growing list of professionals who are moving toward the new standard in design.

Reduce Cognitive Load

Let’s talk about cognitive load, the power of simplicity and how it can increase understanding.

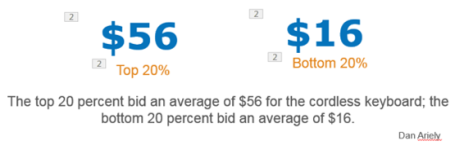

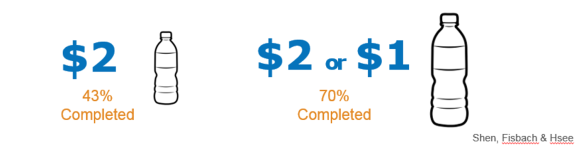

Cognitive load refers to the total amount of mental effort being used in working memory. Rationally, we would think that the more information that a person is given, the better informed they would be; therefore they would make more sound decisions. However, this is not typically the case.

People can become overloaded with information and it doesn’t always provide optimal outcomes.

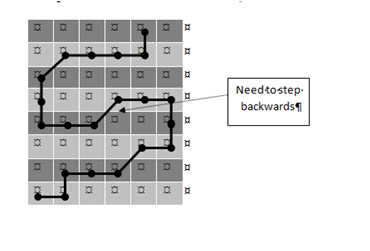

For instance, if we are trying to present the high-level concept of the 4-Drive Model of Employee Motivation, let’s take a look at these two images:

How long did it take you to understand the concept being presented in the first image? How about the second?

The simplicity of the second allows the brain to focus immediately on what’s important.

The first image is hectic, unorganized and does not allow you to focus in on the key concepts being presented. It is important to design so that you present the most important concepts and key takeaways in an easy to understand manner that does not get lost in the ‘fluff’.

In many cases, less really is more when it comes to making sure your audience interprets the message you are trying to convey.

Think of a billboard – you are cruising by at 65 mph (well probably 80 but I’m not supposed to be promoting speeding over here, let’s focus on design and the human brain)… you are cruising by at 65 mph, you glance up to see something that catches your eye but you have very little time to interpret the message.

With this in mind, the designer needs to ensure that the most important and key message jumps out and stays with you. Ask yourself when creating your design, what do I want my audience to understand IMMEDIATELY? Design around that intent and allow the rest of the design to compliment it without taking away from the main point.

So how can you reduce cognitive load in your designs and maximize the impact of the content and messaging? Remember:

Simplify and reduce.

Do you absolutely need to convey that information at this time?

|

White space is good |

Visually represent your ideas.

Visually representing information in an info-graphic or diagram can significantly reduce cognitive load.

Build Consistency and a Strong Identity with The Power of Branding

Creating a consistent brand, look & feel and color pallet within your design helps the audience link to understanding. If your design is part of a larger project, communication or campaign, utilizing a brand throughout the individual pieces creates a mental stamp for the audience to connect the pieces within that campaign.

At the Lantern Group, we have done a significant amount of work in the area of incentive compensation communications. With every client and project that we work on we start with one thing: establishing a brand and a look and feel for the campaign that we will utilize throughout every part of the project.

What we are achieving by doing this is establishing the expectation with our audience that when they see that brand their brain automatically connects it to the content and concept.

Additionally, this can drive increased understanding – seeing that brand can help the user (often subconsciously) trigger what they have already learned in previous communications. These cues and reminders help provide a more immediate understanding of what the content will be and can lay out much of the legwork to capture the audience for you.

Let’s go back to the highway – you are cruising along at 65 mph (I’m willing to bet you think this is a wisecrack about speeding before you even read it, why? Because it feels the same as the previous comment)…

Anyways, you see a large yellow “M” – the golden arches. There is a good chance you already know what the golden arches represent without even needing to see the name of the establishment. The brand is so ingrained in your mind that the link to what you are seeing and what it represents become automatic (a strong established brand).

This same concept can be applied to communications and graphic design!

Now let’s go even further, there is also a good chance that you can remember what that restaurant will look like, what is on the menu, how the ordering process works, etc. The cue has been planted with the yellow “M” and your brain connects the pieces.

Now incentive communications may not be as exciting as a Big Mac, a milkshake, and some fries BUT we can create that same visual cue through a strong brand and increase the power of the information we are presenting. We are allowing our incentive brand to initiate the understanding amongst our audience every time we send out a communication.

You too can have that same impact on your audience when communicating the information you need to get across, the advertisement you are creating, or the logo you are designing by establishing a strong brand.

We hope this has helped you begin to understand the benefits of applying behavioral science to your designs. Next time you begin a design start by establishing a strong brand and evaluating exactly what NEEDS to be portrayed to reduce cognitive load so you can redefine yourself as a behavioral graphic designer.

- Behavioral graphic design is defined as: The profession of visual communication that applies scientific principles dealing primarily with human behavior to the art of combining images, words, and ideas to convey information to an audience and drive human behavior.

This has been just the tip of the iceberg, there are many more ways in which we can apply behavioral science to graphic design to optimize the impact is has. If you want more information on how those ideas are being used by the leading companies in the world, join us – click the links below to follow!

Want to make communications more effective – use behavioral science

Want to make communications more effective – use behavioral science